My father knew all the tricks. Back in the days when turnpike tolls cost 25 cents, he would get off at the exit just before, weave his way through woods and suburbs and reenter the highway at the next entrance beyond. So what if he lost a half hour with his wily machinations? He saved two bits.

Little did he know that he was engaged in a time-honored New England tradition. In colonial days, property owners charged fees - tolls - to pass through their lands on what were the first turnpikes. Those who avoided payment by taking the long way around were called shunpikers. (Or the abbreviation, "pikers?")

To give him his due, my father also loved country roads. Occasionally he would round us up for a Sunday drive. I remember the sinking feeling when I learned we were going on another aimless ramble. I was a kid. What did I care about dumb little towns and pretty views? I wanted to go someplace good and get there as fast as possible.

But the apple doesn't fall far. Decades later, at an age when my father was contemplating abandoning Connecticut for the flatness of Florida, I found myself rolling through a tunnel of pines, maples and oaks toward dark evergreen peaks. And loving it!

This unexpected change of heart took place when I read about a company specializing in backcountry drives throughout the states of New England. It was a siren song calling me home. Especially when I saw the outfit's name: Shunpiking, Ltd.

Shunpiking offered a tantalizing selection of toll-free drives that could be strung together to suit any taste. After much soul searching, I decided on a long weekend in "the Pioneer Valley of Connecticut," "the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts," and "Charming

Vermont Towns." A little over 400 miles in four days. I could handle that.

Early on the first day I picked up my rental car near Hartford in central Conecticut. On the seat next to me I placed a Michelin guide of New England, a map on which I'd Magic-Markered my route and a 68 page guidebook-itinerary created for me by Shunpiking owner, T.J. Harvey. These, along with vouchers for inns where I'd be staying, had

arrived several days before. In the preface of the guidebook I was asked to imagine life as it

was in the early years of our country when "days were filled with toil. Today," I read, "with your comfort, with your relatively easy and secure and peaceful life, you harvest what was planted long ago."

"Ohmygod," I thought. I know that voice!"

My father was a meticulous direction giver, but he had nothing on T.J. Harvey. Paying close attention, I followed his instuctions to "turn R. to Route 20, steer left onto Route 219 and in another 6 miles or so, turn R. onto Route 318."

After a picnic lunch at Barkenstead Reservoir I headed for Pleasant Valley on Route 319. Until now I'd thought of routes as the kind of thoroughfares I was trying to avoid. Not in New England. Calling a cowpath a "route" was the only case of Yankee exaggeration I'd ever encountered.

Sharon, Lakeville and Salisbury were names from my childhood, towns in the northwest corner of Connecticut where I drove past perfectly proportioned white clapboard houses. At any moment I expected a door to open and Jimmy Stewart or Katherine Hepburn to step out and wish me good day.

Crossing into Massachusetts I came to a large house set back behind an ancient stone wall and soon was trying to decide between orange-marinated trout, grilled black angus steak and roasted chicken breast with smoked tomato chutney.

"I love food," said Gail Ryan of the Williamsville Inn. "I didn't make enough money as an actress in New York, so I ended up here."

Ended up running not only a historic country inn and gourmet restaurant, but a sculpture gallery on the outside lawns. I had finished my appetizer when heads turned at the next table. In the garden, stock still among the sculptures, was a tawny doe. No question

about it. The Berkshires were the finest sculptor of all.

I began the second day of my drive by ignoring the Shunpiking itinerary. Sometimes it rains, even on vacation. So I spent the morning with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

The Shunpiking guidebook had me arriving at the Tanglewood Music Festival in early afternoon so I could walk the great lawns before crowds poured in for the evening concert. But since nature had a different pouring in mind, I decided to attend a morning rehearsal.

While musicians ambled on stage in shorts and jeans and t-shirts, I found a seat under the tremendous roof of Tanglewood's music shed. For the next two hours I sat wrapped in the music of Ravel and Mozart played by men and women who looked like joggers come in from the rain.

Then it was time for "some quiet backroading" through a countryside that rolled like soothing sea swells. Judging from the gorgeous estates set on vast lawns, these country roads had come a long way from the days of the horse and buggy.

This small area of Massachusetts is so full of music, art and historic homes that I did less driving and more dropping in - on the Norman Rockwell museum in Stockbridge, for example. The rambling building displayed hundreds of Rockwell's paintings, studies and sketches, from the whimsical early Saturday Evening Post covers to his most famous icons of idealized Americana. Seeing those familiar works was like visiting a favorite old friend. But the sheer size of the operation made me think just a little of Disney in the Berkshires.

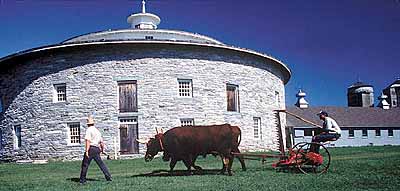

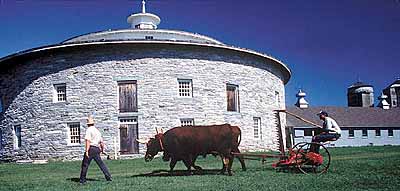

By mid afternoon of day two I was back on schedule, following directions to the Hancock Shaker Village near Pittsfield. Just off the roadway two massive oxen tilled the soil. In rooms where the sexes hadn't been allowed to touch, couples now strolled hand in hand.

For all these years the "brothers and sisters" had produced their incredible furniture, concocted herbal remedies and praised the Lord in their own unique way. Finally they stopped, unable to recruit enough new members to replenish their diminishing ranks. Celibacy had contained its own demise.

Crossing from manicured Massachusetts into rugged Vermont was like entering a time warp. Mountains pressed in, rising steeply from backcountry roads running past scattered hamlets. I could see immediately that Vermont was less affluent than Massachusetts, but also that it had a wild beauty that had been tamed out of its neighbor.

Now I followed a very small road that for once wasn't called a route to the green of Old Benningtom and a white clapboard church. Parking down at the rear, I walked into a graveyard that touched the church on two sides. There were many gravestones there, more than I had expected in such a small town. Some belonged to soldiers who had fallen in the

nearby Battle of Bennington during the revolution. But I was looking for one specific marker and I found it near a single clump birch.

"ROBERT LEE FROST, MAR. 26, 1874 - JAN. 29, 1963," and just beneath, "I HAD A LOVER'S QUARREL WITH THE WORLD." Then, "HIS WIFE, ELINOR MIRIAM WHITE, OCT. 25, 1873 - MAR. 20, 1938. TOGETHER WING TO WING AND OAR TO OAR."

"You should step inside the little Norman Rockwell Museum," the guidebook said as I approached Arlington. "It's much more friendly and intimate than the one down in Stockbridge."

In fact, the Vermont museum had only one original Rockwell, unless you count the hosts and hostesses. "I first posed in 1940 for a Boy Scout calendar," said Mary Immen

Hall, who greeted me at the entrance. "My mother dressed me up in my best outfit. But Mr. Rockwell wanted me to be a flood victim. I'm in my underwear under a blanket."

On the morning of the third day, after downing a feta cheese and asparagus omelet, homemade muffins and fresh fruit at West Mountain Inn where I'd spent the night, I plunged into the Green Montain National Forest. This was my father's kind of country, full of the

trees that turn autumn New England into mountains of flame. But, surprisingly, few of the birches so favored by Robert Frost.

One of several "charming Vermont towns," Newfane was tiny, but posing regally on its green were three massive buildings, a county courthouse with four tall pillars, a spired church and a peaked-roof union hall, date 1832. Less solemn was the country store where a life size teddy bear with a straw hat welcomed visitors.

To reach Weston I climbed past Andover and the Bowl Mill, which T.J. said was filled with household items, "a browser's delight." But since I had all the tea strainers and egg cups I needed, I drove on. Grafton was 6 miles off Route 35 on a road that was not only

unnumbered but unnamed as far as I could tell. When I pulled up at a corner with a 200 year old tavern and a cluster of white houses edged with neat picket fences, I saw that it was called merely, "the Main Street."

Then it was into thick fir forest again, emerging at Tinmouth which seemed to consist almost solely of a lovely white church. Like the churches of classic Vermont postcards it was utterly simple, in the way a pearl is simple.

"Try to arrive at your evening's destination in time to relax before dinner," T.J. advised. This leisurely day, so full of natural beauty, allowed just that, once more at West Mountain Inn.

"From here we're looking at the Green Mountains, "Paula Maynard said. "You know, Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys?" We were sitting, the general manager and I, on a broad lawn that sloped sharply toward the valley below. It was Allen and his men who captured Fort Ticonderoga from the British before the outbreak of the Revolution. Just thinking about it made me tired, or perhaps it was the fresh air. In any event, soon after dinner, it was off to bed.

"The views as you go toward Searsburg are very rewarding," the guidebook promised on the fourth day. "I should hope so," I thought. By now I assumed that rewarding

views were my due. The fact that every few minutes I had to stop to photograph wildflowers or a mountain pond or a miniature graveyard didn't bother me at all. These were simply things you put up with when you go shunpiking. At lunchtime I realized it had taken two and a half hours to drive 60 miles.

"The main thoroughfare of Historic Deerfield is called, simply, The Street," T.J. wrote. "Few streets in America, whatever their names, have the graceful, elegant character this one does."

"There are 13 museum buildings belonging to the historic district," said Karl Sabo, the manager of the Deerfield Inn. "and many private houses and working farms with strict zoning to maintain the character of the village." Part of which is being a member of a community where everyone knows everything about everybody.

"When my wife was pregnant with our first child we wanted to find out which sex the baby was," Karl said. "Jean went to get the mail and the postmaster said, 'Do you want me to tell you what you're having or do you want to wait for the official results?'"

On the fifth and last day I had to shift centuries. It took an hour to return my car on - should I say it? - the superhighway. T.J. had fashioned a tempting alternate route through Amherst and Northhampton, but I had to be home, so I gritted my teeth and joined the anonymous mob.

Did I hate it? Yes, I did. But worst of all was approaching a phalanx of metal boxes straddling the highway, the first toll booths I'd seen in a good many days. Though I knew it was too late, I still kept looking for the last exit off.

A true father's son to the end.

T.J. Harvey offers Shunpiking tours throughout the six New England states. Modules may be combined to create tours of any length. Three types of accomodations are available: "clean and comfortable B & B's, nicer B & B's and country inns, and nice country inns with both breakfasts and dinners." For further information, contact T.J. Harvey, Sunpiking Ltd., 250 Main Street South, Southbury, CT 06488. Tel. 800 695-0115.

When not taking meals at the inns mentioned in the article, the inkkeepers recommended the following restaurants: Near Williamsville Inn. John Andrew. 528-3469. Fine eclectic Ameican. The Old Mill. 528-1421. Similar cuisine, more casual.

Near West Mountain Inn. Chanticleer. Continental. 362-1616. Main Street Cafe. Italian. Chef offers specialized items not on the menu.

Near Deerfield Inn. Sienna. Fine Continental dining. 665-0215. Chandler's Tavern. Basic American fare. 665-1277.

Near Lenox, Massachusetts, Jacob's Pillow presents some of the best dance companies in the world. Get tickets - 413 243-0745 - if at all possible. Music lovers shouldn't miss a morning rehearsal or evening concert at Tanglewood - 413 637-1666.