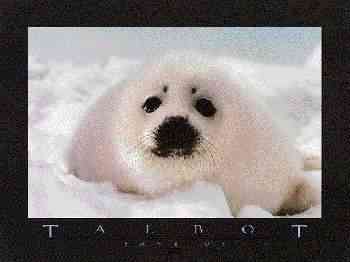

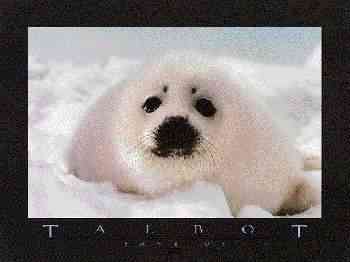

If a fortune teller had told me that somewhere in my future I would be lying on my stomach on an ice

floe staring into the eyes of a newborn seal, I would have recommended Windex for her crystal ball. Yet here I

was, flat on the ice, nose to nose with a bundle of soft white fur with a tail on one end and two black button

eyes on the other. And all around as far as I could see were hundreds of identical copies bawling and

squalling for mommy to bring them some milk.

I had arrived early in March, flying from New York City where it was sunny and warm, to Halifax, Nova

Scotia where the temperature was below freezing and it was snowing. There I joined 21 other seal watchers

on an evening connection to the Iles de la Madeleine in the icy Gulf of St. Lawrence. 45 minutes later we

bumped to a landing in fierce gusts of wind that tore at the snow and flung it against the lights of the

runway.

Next morning at eight we gathered in the briefing room of a hotel which looked over a fleet of

brightly colored fishing boats propped up in the snow. We had come from all parts of the U.S. and Britain,

professors, nurses, a Japanese exchange student, a NASA scientist.

"I know so many people whose brains are turning to mush," said a world-traveling widow. "Their idea

of adventure is going to the mall." Not ours. Young and old, we were as diverse a group as could be

imagined, but we were united by a common desire to witness one of nature's stellar events.

"This is Ben, the demo seal," said our helicopter pilot, John, holding up a cuddly stuffed animal with

dark, soulful eyes. Early each March, he explained, millions of harp seals - named for markings that look

only vaguely like the musical instrument - gather to give birth. One of the breeding grounds was the ice field

not far from where we sat. Each baby, John said, is identified at birth by its mother in a nose-to-nose sniffing

procedure and immediately gets down to the business of putting on weight. This it does - four pounds a

day - a testament to mother's milk. For the next two weeks it's nothing but eat and sleep until the baby is

abruptly weaned, momma disappears through the ice and the pup's cries go forever unanswered.

"Don't get between a mother and her pup," John warned. "They're much faster than you and they

bite." With those encouraging words we struggled into heavy orange expedition suits with the word

"Sealwatch" emblazoned on the back and stepped out into the cold.

We'd been told that the wind chill factor was minus 30 to 40 degrees, numbers I found

incomprehensible. Suddenly they had profound meaning. Any exposed skin, a tiny ribbon of wrist, my entire

face, immediately felt frozen.

Genderless and featureless (faces having quickly been covered by masks and scarves), we stumbled

into the helicopters. In seconds we had left the island behind and were flying low over a flat whiteness broken

only by black water showing through cracks in the ice. Geometrical ridges stitched great floes together, snow

drifted in white longtail patches or lay sculpted like frosting spread with a mammoth cake knife.

"There's a seal down there!" someone cried.

We banked sharply, descended and saw, scattered on the ice, the unmistakable oblongs that had

fascinated us when we were kids at the zoo. Then we noticed, trailing behind, small white shapes scurrying

away from the noise. We had arrived.

We hopped onto the ice, gingerly because we could see holes in it with snub-nosed heads poking out.

And while the seals seemed comfortable enough in the water, the thought of joining them didn't appeal.

The cake-frosting landscape opened out before us, great chunks of iron-hard ice encrusting frozen ponds. We

were lost in an unbroken circle, infinite, harsh and beautiful

Everywhere we looked were seals, big ones, fat and sleek and grey, and little white ones sprouting

hairbrush whiskers. Out came the cameras and soon the immediate neighborhood was dotted with bulky

orange bodies clicking furiously away. The initial frenzy lasted about 30 minutes. Then we realized that the

seals weren't going anywhere and neither were we for that matter, at least for a couple of hours, so we

relaxed and began to enjoy the incredible experience.

The baby harp seals - "whitecoats" - were actually not identical. The youngest of them were thin and

yellow and still carried the tattered red remnants of umbilical cords. Those a few days older, having

gorged themselves on fat-rich milk, were round and fluffy white. Some of them yelled in protest when we

approached and tried to flee by pulling their limp bodies with the claws on their flippers. Others came straight

up to us, staring with pitch black eyes, and were happy to be petted (but not as happy as those who did the

petting).

While many babies napped, more cried plaintively. Most were alone, calling for their mothers, though

a number of female adults lolled by their offspring and glared warningly whenever we came too close. Many

more mothers were underwater and would pop up from blow holes, take a look around and disappear again.

Several times I saw a large grey seal go to a crying whitecoat, realize that it wasn't hers, and leave the poor

waif hungry and unhappy.

Many places in the ice were stained with red-brown patches of blood, signs of a recent delivery. In a

very real way it was blood that was responsible for our being here, not the blood of birth but the blood of

death. Until recently, almost a quarter of a million seals, mostly babies, were slaughtered each year for their

skins on the ice floes off the east coast of Quebec. Armed with baseball bats, islanders invaded the herds,

clubbing the whitecoats to death. To be fair, the seemingly brutal act was quick and effective, probably more

humane than shooting, and no more deadly than killing cod.

But fish don't have imploring black eyes, and in 1969 a Canadian named Brian Davies founded the

International Fund for Animal Welfare in a determined effort to stop the killings. Amazingly, he did. 20 years

after pictures of the hunt appeared in the world's newspapers, the European Community banned the port

of baby sealskin products and the market collapsed.

So did the income of the seal hunters of the Iles de la Madeleine, which is where Natural Habitat

Adventures enters the picture. "The idea behind Sealwatch is to provide an alternative income for the

inhabitants of the islands," said Ben Bressler, the director of the company.

Each year since 1988, when Natural Habitat began bringing tourists to the breeding grounds, more

money has been added to the local economy than in the days of the hunt. But those immediately

benefitting were hotel and restaurant owners, not hunters. And now a new market for seal products has

opened in Asia and the Canadian government has partially lifted the ban on hunting. The story with a

happy ending has another chapter to run. So it was with a certain sense of urgency that we made our trips

to the ice. And a feeling of foreboding informed the lectures and slide shows given by Natural Habitat's young

staff of dedicated experts. But never gloom. They were a jovial lot, outdoorsmen and women, revelling in their

work which on non-trip days included cross country skiing, snowshoeing and evening hikes.

But as invigorating as all the extras were, nothing compared with the sealwatch. Succeeding trips to

the colony were even better than the first. Now we were accustomed to being on the ice, even if it was

shifting beneath our feet. We could devote all our attention to the seals, could stay for long minutes in one

spot, close enough to listen to the sounds of nursing. We could root for the hour-old baby making fumbling

attempts to find its bottle and silently cheer when it did.

We'd been told that the whitecoats didn't play, but I watched one burrowing madly into the snow and

it certainly looked like it was having fun. Another lay on its back, eyes closed in ecstasy, and gave itself a

good scratch. I guess he knew where it itched.

We could even forget about the seals for a moment and take in the amazing landscape: the clumps of

ice thrusting upward and gleaming blue in the sun, the pure whiteness of the snow, so dry that it brushed

off cameras and clothes like sawdust. Ever more confident, we ranged far afield. Distant orange shapes

inched over the desert white like moving spots of color. As the sun dropped toward the horizon, shadows

lenthened and turned steel-grey. It was hard to believe that this most peaceful scene once was, and

could be again, a killing ground.

But for now the whitecoats were ours to watch, to listen to, and even, when they wanted us to, to

touch.

HOW TO GET THERE: The Sealwatch officially begins in Halifax, Nova Scotia where a charted jet flies

participants to the Iles de la Madeleine. Airlines flying to Halifax from the States are Northwest Airlines

(nonstop from Boston) - 800 225-2525, Air Canada (nonstop from Newark, NJ, Boston, Montreal and Toronto) -

800 776-3000 and Canadian Airlines (no nonstops) - 800 426-7000.

WHEN TO GO: The Sealwatch programs operate anually during the first three weeks of March.

WHAT TO WEAR: Very casual clothing is appropriate for dining. For seal watching, expedition suits and

boots are provided as well as cross country ski equipment and snow shoes. Bring the best available long

underwear, wool socks and hat, heavy gloves or mittens and glove liners, a warm sweater, heavy shirts, warm

pants, scarf, and sunglasses. A protective mask for the face is highly recommended.

PHYSICAL FITNESS: Visits to the harp seals do not require a high degree of physical fitness.

Handicapped travelers are welcome. Other outdoor activities are offered at varying levels of fitness.

OPTIONAL ACTIVITIES include cross country skiing, photo-workshops, nature hikes, showshoeing, tours

of the island and visits to local craftspeople. Slide shows and lectures are presented daily.

PHOTO GEAR: Most people use point-and-shoot cameras. While a standard lens will provide excellent

photographs, professionals use wide angle and telephoto lenses as well. Relatively slow speed films are

recommended, Velvia being a favorite.

WEATHER being unpredictable, there is always the possibility of Sealwatches being canceled. Travelers

on a strict schedule should also be aware that bad weather can delay flights to and from the Iles de la

Madeleine.

ACCOMODATIONS are in modest but comfortable hotels.

FOOD on the island is mediocre.

NATURAL HABITAT ADVENTURES, in addition to Sealwatches, operates "watches" for polar bears in

Canada, New England wildlife, whales in the Baja, the Azores and the Arctic, dolphins in the Bahamas, brown

bears in Alaska and wildlife in Hudson Bay, Costa Rica and the Galapagos. There are also trips to Antarctica

and "researach adventures" to Scotland's Shetland Islands and a wolf watch in Canada. All of these are

personally escorted by a permanent staff of scientists and young outdoor professionals. More recent trips, for

which Natural Habitat uses carefully chosen local suppliers, are wildlife programs in Kenya/Tanzania,

Namibia, Botswana/Zimbabwe and primate watches in Rwanda/Zaire and Borneo.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION contact Natural Habitat Adventures at 2945 Center Green Court South, Suite

H, Boulder, CO 80301, telephone 800 543-8917.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION ABOUT THE INTERNATIONAL FUND FOR ANIMAL WELFARE, write IFAW,

P.O. Box 193, Yarmouth Port, MA 02675.